U.S. National Parks are home to some of the most breathtaking scenery in the world, but the history these protected lands share with U.S. railroads may be surprising.

As railroads expanded passenger service westward in the 19th and 20th centuries, they enticed visitors to travel to these then-unknown destinations. Expeditions had already revealed the unique geography of the land, and the government was taking steps to protect the natural beauty of what would become some of the world’s most famous landscapes. Families began to flock to today’s national parks.

Here’s how BNSF predecessor railroads helped shape and protect the grandeur of these landscapes.

Yellowstone National Park

Even before Yellowstone would become America’s first national park, tales of the area’s otherworldly geography had already reached the East, thanks to descriptions by John Colter, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. His descriptions inspired the Washburn Expedition in 1870 and the geological survey by Ferdinand Hayden in 1871 that would prove instrumental in the park’s creation.

Details from these expeditions piqued the interest of Jay Cooke, the financier of the Northern Pacific (NP), and other investors. They saw an opportunity for the railroad to attract tourists to their planned route to the Puget Sound. By advocating for a public recreational area created from the land that is now known as Yellowstone National Park, railroads could secure profit from tourism in an otherwise desolate part of the West.

After the Yellowstone Act of 1872, which established Yellowstone as America’s first national park, the land remained a sparsely visited site until the NP reached the northern rim in 1883 with the completion of its branch line in Cinnabar, Montana.

Once the line was completed, NP began advertising the route with paintings by renowned artists such as Thomas Moran to entice visitors to come witness the majestic views for themselves. One advertisement, created by NP’s Passenger Agent Charles S. Fee, likened Yellowstone’s wilderness to something out of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Fee created a tourism guidebook, Northern Pacific Railroad: The Wonderland Route to the Pacific Coast, detailing his personal experiences and the area’s amenities.

As visitors to the park increased, NP provided new amenities to compete with the other railroads whose lines had reached the park’s boundaries. NP expanded its line to Gardiner, Montana, allowing direct access to the park, and built hotels to accommodate passengers during their visit.

The Old Faithful Inn

Most notable was the construction of the Old Faithful Inn, built between 1903 and 1904 by architect Robert C. Reamer, that still stands near the famous geyser. Over the years, the hotel has been host to numerous guests, including President Theodore Roosevelt, whose influence on the park is recognized with the Roosevelt Arch outside of the Gardiner Depot.

With the success of the railroad’s venture into Yellowstone National Park came concern that opening the area to industry would diminish the natural beauty that was now protected under federal law. However, Fee, who remained in his position until 1905, pledged that the railway would work to preserve the park. That pledge was further embedded in the shared history of Yellowstone National Park and the NP in 1893 with the unveiling of the railroad’s new logo, the quintessential yin and yang symbol meant to represent the balance of the two endeavors.

Grand Canyon

Although the Grand Canyon was only recognized as a U.S. National Park in 1919, the history of tourism in the area dates to 1869 when it was originally declared a forest reserve by President Benjamin Harrison.

At that time, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad (ATSF) was running from Chicago to Los Angeles, passing through Williams, Arizona, to serve local copper mines. If tourists or adventurers from the East desired to make the arduous trek to the canyon, they would ride the ATSF to Williams before disembarking and catching a stagecoach for the last eight hours of the journey.

In 1901, the journey became much simpler when the ATSF acquired the local Santa Fe and Grand Canyon Railroad Company and completed the remaining 65 miles of a spur track to the canyon’s South Rim, now known as Grand Canyon Village. Here they built the Grand Canyon Depot, which still stands today, as well as several other historical lodges and buildings to accommodate guests.

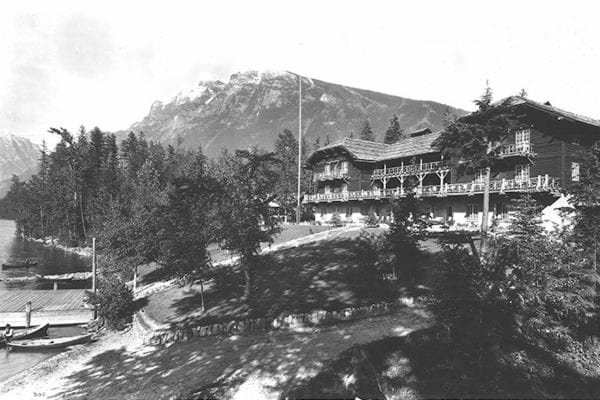

Often, the ATSF would pair with its well-known Fred Harvey Company partner to provide luxurious accommodations and dining options (served by the Harvey Girls ) to visitors. The same was true with the El Tovar Hotel. Opened in 1905 and designed by architect Charles Whittlesey, the hotel’s style, like many of its counterparts, was inspired by Swiss chalets and other European destinations that wealthy visitors from the East frequented.

The El Tovar Hotel past and present.

One of the largest hotels of its time, the El Tovar featured 95 rooms that accommodated nearly 200 guests. The Fred Harvey Company and ATSF would go on to hire Mary Jane Colter to build a number of buildings surrounding the Grand Canyon, including the Bright Angel Lodge, the Hopi House and Lookout Studio, among others.

Many of these structures still exist today, and travelers can experience the same trip as those who came before on the Grand Canyon Railway, a historic railroad that has been fully restored.

Glacier National Park

It’s nearly impossible to consider the rise of the railroad industry and how it populated the Midwest without including entrepreneur James J. Hill.

The Great Northern Railway (GN) was founded by Hill in 1889 after he acquired the St. Paul and Pacific and the Minneapolis and St. Cloud railways. The lines extended west through the Rocky Mountains and the famed Marias Pass in 1891, reaching the Pacific Ocean in 1893 by way of Scenic, Washington.

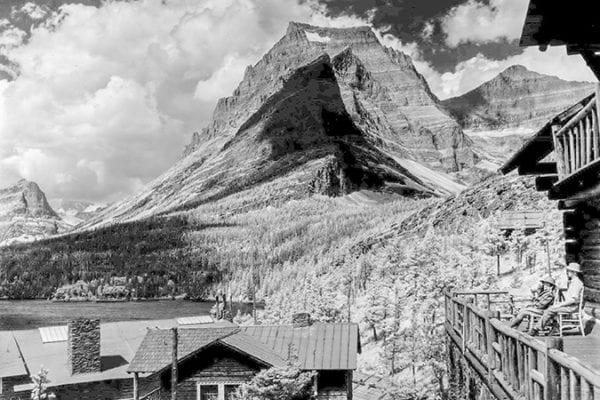

In 1907, Louis Hill took over the GN as president before his father’s retirement in 1912. Together, they shared a dream of making their network the “Playground of the Northwest,” including the area that would become Glacier National Park.

Like his father, Louis had a mind for business and focused on the expansion of GN’s passenger service. He and his father advocated for the creation of a national park where the Rocky Mountains reached the Canadian border, known now as Glacier National Park. Ultimately GN benefited from providing transportation and lodging to tourists traveling westward.

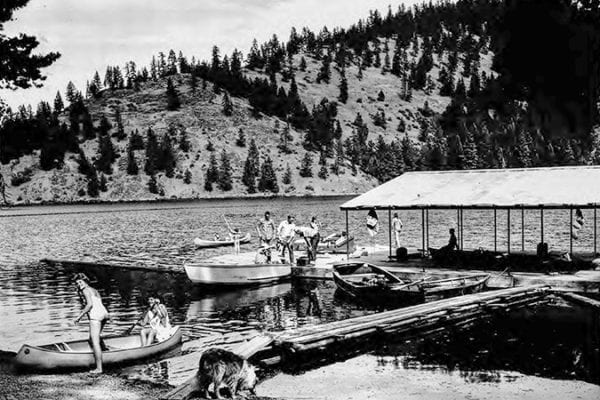

Glacier National Park was established in 1910, and GN continued to invest in the area, creating hiking trails for guests and building luxurious hotels modeled after the chalets of the French and Swiss Alps. Many of the hotels are available today, like the Lake McDonald Hotel, Glacier Park Lodge and the Sperry Chalet.

Hill advertised a visit to Glacier National Park via rail as the “ultimate American experience,” using the slogan “See America First.” He successfully enticed tourists more accustomed to the perceived refinement of European vacations to visit the natural wonders in their own backyards.

Today, Amtrak’s Empire Builder route, named in honor of James J. Hill, follows GN’s original transcontinental line, giving passengers an opportunity to visit Glacier National Park as travelers did in the past.

This article originally appeared on BNSF’s RailTalk.